New Data Reveals Barriers to Sport for Minority Communities

Despite the growing awareness of the importance of physical activity for mental and physical wellbeing, new data reveals that significant gaps remain in who has access to and feels welcome in the world of sport.

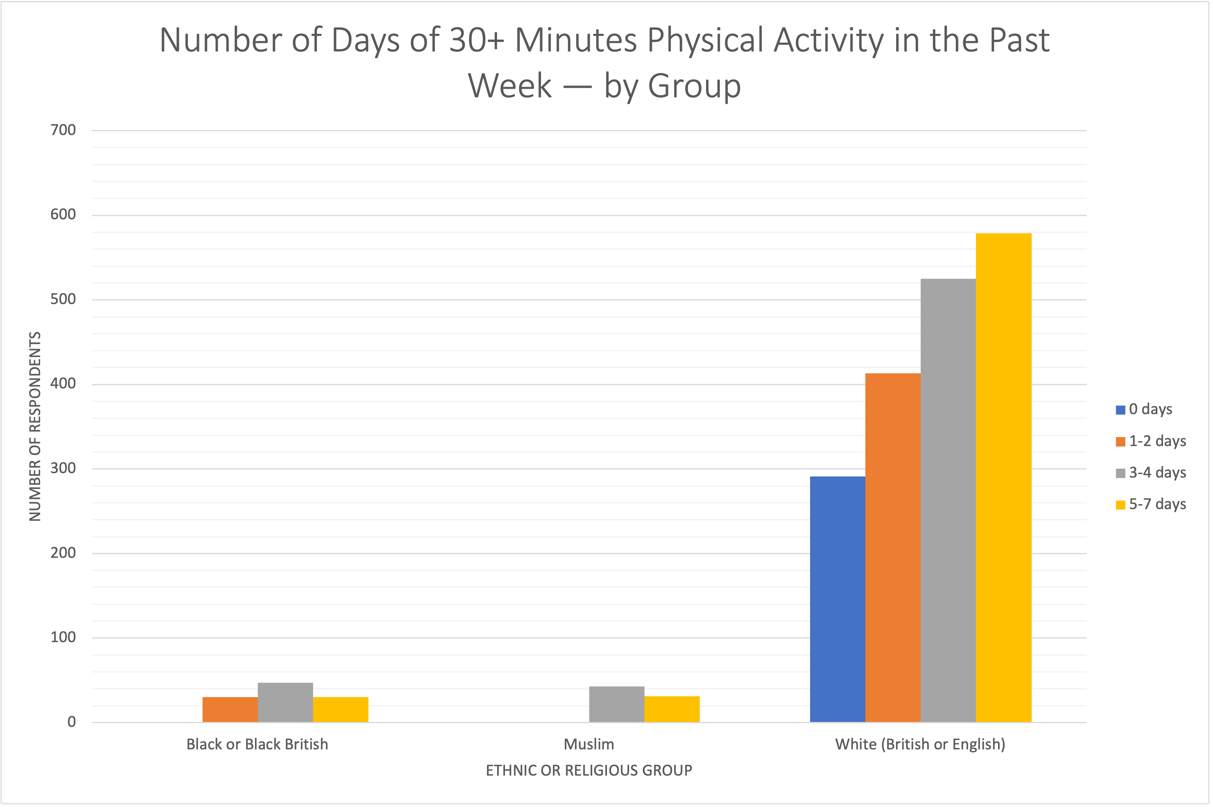

Data shows that white (British or English) individuals are 15 times more likely to engage in 5-7 days of exercise compared to their BAME counterparts.

Questions have been raised around access to exercise opportunities due to cultural or structural barriers.

Active Lives Survey

Sport England’s latest Active Lives survey reveals that people from minority ethnic and religious backgrounds are still not meeting recommended physical activity levels each week.

Sport England argues that reasons for these disparities go far beyond personal choice, with a follow-up publication from the Active Lives survey highlighting that they are often driven by structural causes:

“A person’s age, sex, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic group, whether they have a disability or long-term health condition, and the place they live in are all significant factors impacting our relationship with sport and physical activity”.

The report shows that many longstanding inequalities remain, with women, those from lower socio-economic groups and Black and Asian people still less likely to be active than others.

Barriers to Access

Many people from ethnically diverse backgrounds report feeling disconnected or unwelcome in traditional sporting spaces.

Research shows this isn’t just perception — 40% of Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) participants reported having negative experiences at local sports or leisure clubs, compared to only 14% of white British participants.

Moreover, over half (55%) of people from minority backgrounds said they would be more likely to get involved in sports clubs or volunteer if better, more accessible information about local opportunities was available online.

A lack of representation, unfamiliar environments, and cultural insensitivity all contribute to a sense of exclusion, creating a cycle of disengagement where individuals are either unaware of local opportunities or feel those spaces “aren’t for them.”

Ellie Bradwell of Sporting Equals, a UK charity focused on promoting racial equality in sport, explained how, in this day and age, there is often a lack of understanding around why people might not feel able to take part.

“It could be about cultural sensitivities, the timing of activities, or access to modest clothing — all small changes that can make a huge difference in creating welcoming environments.”

-Ellie Bradwell, Sporting Equals

These challenges are not just confined to adults; they also manifest in the experiences of young people, where the impact can be even more significant.

Inequalities amongst young people

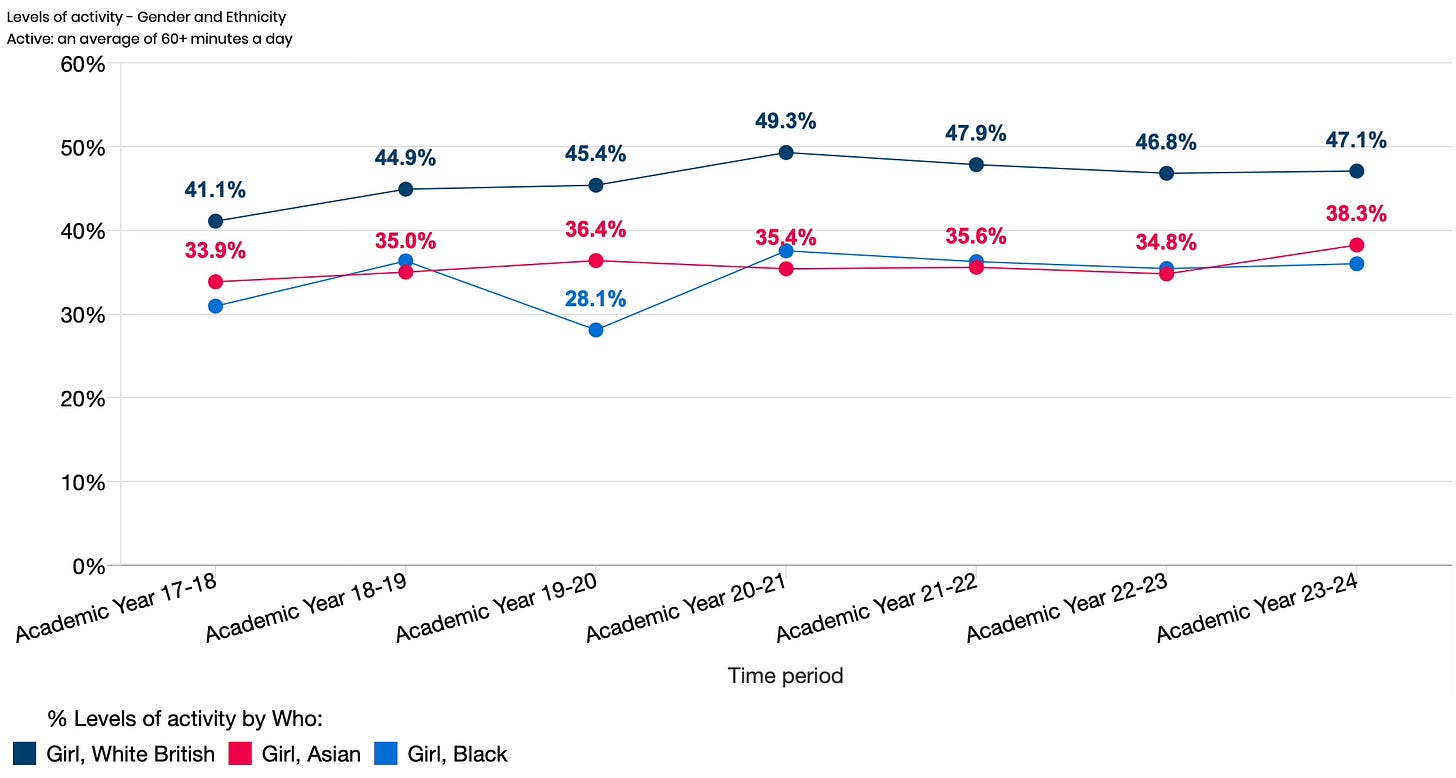

The Children and Young People Active Lives survey shows that children from ethnically diverse backgrounds, particularly girls, are less likely to reach their recommended weekly activity levels — a gap that risks widening over time if action isn’t taken.

A line graph showing physical activity levels of girls at secondary school from 2018-2024, with asian and black girls reporting significantly lower levels - taken from The Children and Young People Active Lives survey.

A line graph showing physical activity levels of girls at secondary school from 2018-2024, with asian and black girls reporting significantly lower levels - taken from The Children and Young People Active Lives survey.

Khadija Patel serves as a volunteer and chairperson for KRIMMZ, a Bolton-based community organisation that primarily provides support for its Muslim residents.

The group offers a wide range of enrichment opportunities, from workshops to an extensive selection of sports, designed to provide opportunities that are often otherwise out of reach for members of the local Muslim community.

“At KRIMMZ, it’s all about making sure that our community have access to sports that they are comfortable taking part in, ensuring that their religious cultural sensitivity needs are fully met.” - Khadija Patel

Data from the Youth Sport Trust’s Faith and Culture Report, explores how young people from different religious backgrounds engage with physical activity in the UK.

The report highlights key statistics around enjoyment and barriers — particularly for Muslim girls, 28% of whom report feeling uncomfortable in mixed-gender PE classes, making it a significant obstacle to school-based sport.

KRIMMZ acknowledges the specific needs of these individuals.

At the core of their approach are the three Ps: provision, privacy, and prayer.

Khadija highlighted a simple but often overlooked barrier: traditional after-school sports schedules don’t fit the lives of many Muslim children, who typically attend Mosque classes between 5 and 7pm — meaning they miss out on most clubs.

KRIMMZ steps in by offering flexible evening sports sessions designed around the community’s needs.

Representation, Khadija says, is just as important as timing: “If they look like them, they see them.”

She adds that when young girls see a hijab-wearing netball coach, it builds trust with both children and parents: “It gives parents confidence knowing their daughters can take part without compromising their religious values.”

As participation gaps persist, the work being done at the grassroots level can no longer be seen as unimportant. Organisations like KRIMMZ are actively reshaping what access and inclusion look like for communities that have long been overlooked.

By tailoring their approach to the real lives of Muslim girls through flexible timings, culturally sensitive coaching, and creating safe spaces, they’re removing barriers that national policies too often fail to address.

Adopting a culturally and structurally aware approach to offering sports in various communities has had a positive effect on many, including those at KRIMMZ.

Targeting adults within these minority communities in similar ways could help bridge the disparities revealed by the data, though challenges remain in fully addressing these gaps.

Post a comment